North African energy dilemmas (1/2)

Will Algeria lose its gas moment?*

Italy and Europe look to Algeria to reduce their dependence on Russian gas, but the north African country’s lack of strategic economic thinking and constant tinkering with rules in the energy sector have reinforced the perception that it is an unstable partner.

Understanding history is essential

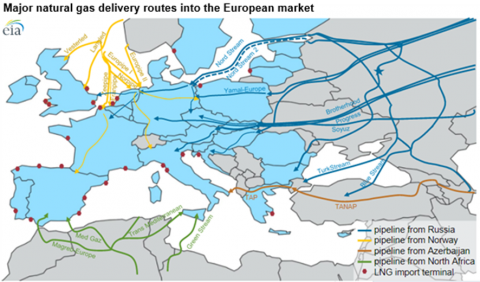

With about 8% of the market share, Algeria is Europe's third-biggest natural gas supplier. It has direct pipelines to Italy and the Iberian Peninsula. It also supplies gas in Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) form to France, Belgium, the UK, Greece and Turkey. It has always honoured its contracts since it started exporting gas to the UK in 1964. As Italy has been working to reduce its dependence on Russia, it has been looking to Algeria, its second-largest gas supplier, which has agreed to increase its deliveries to reach 30 billion cubic metres per annum by 2024 rather than the current level of 21. Whether it can seize the moment offered by the war in Ukraine as Europe’s Faustian pact with Putin unravels spectacularly will depend on the capacity of the country’s rulers to construct a long-term strategy. That will only happen when they rewrite the rules of the command economy which have prevailed since independence 60 years ago.

Algerian leaders can afford to put off reforms for now because of the disarray of European leaders who are finding it difficult to find new sources of gas supplies (there are precious few in liquefied form) even at current sky-high prices. As they ratchet up sanctions on oil against Russia, EU politicians are discovering that the boomerang effect on their economies might be worse than any damage they inflict on Russia. This in turn suggests the conflict will be long. Meanwhile, seasoned gas observers agree that Europe’s energy crisis will play out over years, not months, one meaning of the boomerang effect.

Former president Chadli tried and failed to move Algeria out of the pit of autocracy by launching, in 1988, what he fully realised were revolutionary economic and political reforms. His military peers put a stop to them, using the emergence of the Islamic Salvation Front to scare the middle classes into supporting a repressive policy which provoked a civil war that claimed more than 100,000 victims. Other Arab rulers have used similar strategies with similar disastrous consequences.

Algeria’s Jurassic style of economic management is a victim of the oil curse. It cannot offer a solid bedrock for domestic stability and faster economic growth. So long as the military refuse to allow the middle classes to partake in the debate on the country’s future and develop a vibrant private sector, any attempt to liberalise the economy will fail. The impact of reform in the energy sector will be limited in the absence of fundamental reorganisation of the architecture of power in Algeria.

That rested for decades on a tripod which included the army, the security forces, and the senior bureaucracy, which included Sonatrach. Misrule under Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who was president from 1999 to 2019, eviscerated the senior bureaucracy and promoted crony private capitalism. The result was a massive flight of capital. Bouteflika’s determination to seek a fifth mandate in 2019 despite being very sick provoked massive demonstrations. Known as Hirak, these peaceful protests (which included slogans such as “only Chanel does No 5”) were quelled by a combination of harsh repression and Covid19 which handed supreme power to the army.

A long-term energy strategy has been lacking ever since the powerful minister of energy Chakib Khelil was dismissed back in 2010. The minister who was very close to Dick Cheney, then vice president of the US and a founder of Halliburton, failed to liberalise the energy sector because his policy was bitterly opposed by an unlikely coalition which brought together the Algerian establishment, the King of Saudi Arabia and the Russian president. They alleged that Bouteflika was “selling the family silver to American interests” . Both the king and Vladimir Putin warned their Algerian counterpart against the policies of Chakib Kheli which they considered detrimental to OPEC and other non-western producers of oil and gas.

Allegations of corruption have clung to Khelil and senior executives of the state oil and gas monopoly, Sonatrach ever since. Its once-proud reputation has been weakened. More than a decade of musical chairs in a sector which provides 97% of Algeria’s foreign income and two-thirds of its budget receipts has weakened a once proud company as foreign partners have grown weary of ever-changing fiscal terms and slow decision-making.

The stake Sonatrach had acquired in regasification plants abroad and other tools which boosted its capacity to commercialise its gas internationally have been degraded, thus depriving it of some of the benefits of today’s higher prices. Covid19 delayed the response of international companies to the new law liberalising foreign investment which was enacted in December 2019. Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi (ENI) signed a new cooperation agreement with Sonatrach in November 2021. Previous oil and gas licensing rounds since 2014 had prompted little interest from international companies but that is no longer true as high prices have prompted many western companies to rush to Algiers and offer ample funds to develop existing and new oil and gas fields. History has dealt Algeria very good cards just as the new management of Sonatrach was injecting more stability in the rules of management than at any time in recent years. Structural reform is not, but the growing presence of ENI will help only because of the deep trust between the two companies. ENI advice has a better chance of being taken into account than that of any other foreign company.

[Europe relies primarily on imports to meet its natural gas needs - Today in Energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)]

The energy sector cannot be reformed in isolation

The policy of showering subsidies on consumers when the price of oil is high and making unexpected and deep cuts when it falls has been pursued for forty years. It has seriously weakened the industrial base the country built in the 1970s. Fifty years ago, the minister of industry, whose remit included energy could boast that “Algeria will be the Japan of Africa in the year 2000.” Nothing of the sort happened and Algeria’s military never learnt the lessons from the economic success of countries such as China, South Korea and Turkey. It persists in its refusal to allow major Algerian companies to integrate into the world market. Many private entrepreneurs, economists and engineers have left a country which excels at cannibalising its elites.

For a generation, Algeria has been deindustrialising. Investment in industry amounted to 30% of GDP until the early 1980s. Today it amounts to less than 10% - compared to an average of 30% in emerging Asian economies. The economic ambitions of Algeria’s second president, Colonel Houari Boumediene (1965-1978) may have been exaggerated but he must be turning in his grave when he contemplates the economic illiteracy of his successors. The result is that the next generation is being deprived of jobs and, as important, of hope. Enhancing its role as a gas supplier to Europe would offer the country more regional influence.

Over one hundred joint ventures - outside the hydrocarbons sector - were signed between Algerian state companies and international corporations when bold economic reforms were launched a generation ago. Modernising the rules of engagement in the energy sector was responsible for a large increase in foreign investment, production and exports, despite the bitter ongoing civil war. A highly qualified Algerian diaspora has emerged in Europe and the Gulf since the 1980s. Its members would welcome the opportunity to insert Algerian companies into global networks of trade and investment.

How can reforms in the energy sector be made to work?

There are plenty of new gas reserves to be found in Algeria. Natural gas will continue to play a crucial role in the energy transition, but LNG cannot play the role of “variable d’ajustement” the EU wishes it to in a market which has been liberalised. Having promoted, from 1998 a policy to liberalise its gas markets, the EU is hoisting on its own petard. Extra supplies of LNG are scarce and expensive. The war in Ukraine, however, offers Algeria a unique opportunity to modernise its energy sector and, by developing the production of hydrogen, ammonia and solar power, to insert its economy into global networks. Do Algeria’s leaders appreciate that a well-equipped army is no substitute for a diversified and open economy? That is open to doubt but the officer corps is very well trained. It attends foreign military academies in Russia, France, Germany and Italy. Second, guessing whether the economic philosophy of the officer corps will evolve in the future is a mug’s game.

The outlines of Algeria’s energy problem lie in plain sight. Gas is supplied to Sonelgaz, which has a monopoly on the production and sale of electricity at less than $0.30/MMbtu, a price which does not cover Sonatrach’s production costs. The efficiency rate of its old power plants is very low (around 36%) and grid losses are high. Exports will start to decline after 2025 due to a lack of output and could grind to a halt after 2030 as production may have to be reserved for domestic consumption.

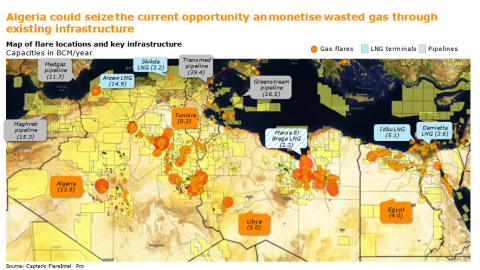

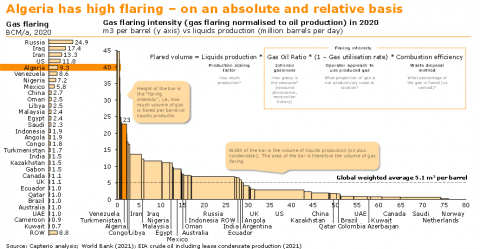

Current gas production of 130 bcm is divided into three almost equal parts: consumption, export and reinjection, but a recent report highlights a point which has long been overlooked. “By capturing gas from flaring, venting, and leaking in the region, Europe could within 12-24 months start to substitute up to 15% of Russian gas” which would also allow gas producers to “significantly reduce CO2-equivalent emissions without delaying the energy transition and greatly benefit from new revenue streams to reinvest in clean energy sources.” (1) The scale of this underappreciated “supply source” of wasted gas is staggering. It amounts to 260 bcm per year worldwide. And for Algeria, this was around 9 bcm in 2020, with gas ‘flaring intensity’, at twenty-three cubic metres per barrel, more than four times the global average. The irony is that much of this flared, vented and leaked gas could only be captured with proven solutions that make money, but also could be exported to Europe via the two pipelines and two LNG terminals, which in the aggregate are dramatically underused. Sonatrach has recently acknowledged the problem of flaring publicly and said they were seeking solutions.

No blueprint for reform has any chance of succeeding if it fails to gain broad popular support. There was near unanimity in 1971 when Algeria nationalised foreign oil and gas assets. One only needs to recall the failure of Khelil’s attempt to liberalise in 2005 and the protests which greeted the government’s decision to start exploiting unconventional gas resources which broke out in 2015 and again in 2020. The research permit to exploit shale was granted to Halliburton which was forced to liquidate its Algerian subsidiary after billions of dollars of over-the-counter contracts it had signed with local partners, notably the ministry of defence came to light.

Any overhaul of Algeria’s energy policy will have to tackle the very political question of subsidies. Algeria’s leadership has always traded cheap prices of staple food and energy in exchange for the acceptance of autocratic rule. The Hirak demonstrated that millions of Algerians wanted a say in their country’s future. Structural reform will be impossible without a popular debate. But since there is no space for public debate, foisting structural reform on Algerians without it would be a recipe for more instability. Fobbing off people with a new law enacted after a debate in the national assembly is sure to fail.

Oil and gas nationalism has been strong in Algeria because of the country’s bitter fight for independence. That came in 1962, two years later than might have been the case because President Charles de Gaulle tried to detach the Sahara, where oil had just been discovered, from the newly emerging nation. It was the founder of ENI, Enrico Mattei who advised the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic during its negotiations with France in 1960-1962. Many Algerians remain hostile to the idea of private Algerian capital ever playing a role in this sector. Foreign investment is often viewed with suspicion, but there is little informed public debate on the subject. This only encourages conspiracy theories. Yet more and more Algerians understand that international companies have historically made a very positive contribution to the building of the energy and industrial infrastructure. Nor are they blind to the role private Algerian entrepreneurs could play in the energy sector

If Algeria seizes its gas moment, that will help to enhance Italy’s key role as a gas hub (2) in the Mediterranean and encourage it to play a more ambitious and independent role in shaping Europe’s policy towards the region. As for Algeria, it can only blame itself if it fails to rise to the historic challenge it faces and loses a unique opportunity to enhance its energy and industrial cooperation with Europe.

(1) North Africa can reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas by transporting wasted gas through existing infrastructure, Mark Davis (Capterio), Perrine Toledano and Thomas Schorr (Columbia Centre on Sustainable Investment at Columbia University) 29 March 2022.

(2) Spain aspires to become an Iberian corridor of gas to countries to its north. With an extensive network of LNG terminals, Spain and Portugal’s regasification capacities represent around one-third of Europe’s capacity. Half of this is not used. The first challenge Spain faces is the resistance of the French nuclear lobby to the trans-Pyrenean pipeline being expanded. This is now a priority for the EU but calls this summer from the German chancellor to turn Spain into an EU gas hub as, so far, fallen on deaf ears in France. Were France to change its position, it could take five years before a new Spain-France pipeline is being commissioned. The pipelines from the Iberian terminals to the frontier would also have to be upgraded.

In the first six months of this year, Spanish companies purchased 42% less gas from Algeria than a year before and 19% more Russian gas At the turn of the year it was importing an annual equivalent of 8.7 bcm through the Medgas pipeline, whose capacity is 10 bcm/annum. Flows through the second gasline which connects Spain with Algeria via Morocco (GME) have been suspended since 1 November 2021 due to diplomatic tensions between the two north African countries. Morocco for its part is purchasing LNG through a German company, landing it in Spain which then sends it south. Such reverse flows are not uncommon in international gas pipelines but the gas Morocco purchases in this manner are no doubt more expensive than what it received from Algeria until 1 November 2021.

Italy, on the other hand, is much better placed than Spain to act as an EU gas hub. Four factors stand to strengthen its role as the major southern gas hub of the EU. First are the three gas pipelines, from Azerbaijan, Libya and Algeria that bring gas from three different sources to the south of the country and the location of the depleted gas fields of the Po valley which offer a perfect place to stock gas. Second, Italian imports of gas are six times higher than Spain’s. Third, Italy boasts some of the best technology on offer in the world for building refineries, LNG plants and underwater pipelines, which is not the case in Spain.

A fourth factor is coming into play as Germany is showing interest in purchasing Algerian gas. Back in 1978, Germany and Holland contracted to buy Algerian LNG and build the necessary regasification terminals. That would have diversified both countries’ non-EU suppliers of gas when the Yamal pipeline was being built, the first pipeline which would be built to bring Soviet gas to Europe. The US feared that construction of the pipeline would lead to Europe’s becoming dangerously dependent on Soviet gas. The US tried to convince the Europeans there was alternative, more liable sources, one of which was the giant Troll field in Norway. According to Allen Wendt, a retired US ambassador, in a letter to the Financial Times in 2014, the Europeans argued that other sources of gas the US had suggested, such as Algeria, were no more reliable than the Soviet Union. The US was actively promoting the idea of an Algeria to Spain pipeline at the time. The then Director General of the Ministry of Energy and Mines in Algeria, Sadek Boussena, who became Minister of Energy from 1988 to 1991, says that the reasons why Germany did not implement the contracts were never made clear. Holland explained it could not proceed if Germany did not.

My understanding is that Germany came to the conclusion that the cost of importing LNG -the building of regasification terminals and LNG ships were simply too high. Piped gas from Russia was much cheaper

Francis Ghilès

Member and contributor to the Frontier Energy Network, the world-leading network...

Voir l'auteur ...